The Science of Sticking to Your New Year’s Resolution - The Theory of Planned Behaviour - Feelings of Control

Theory of Planned Behaviour

The next theory of behaviour change we will look at on our quest to add some science to New Year’s Resolutions is the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB).

Like the other theories we have looked TPB places an emphasis on how our social world affects our behaviours and our ability to change them.

The theory of planned behaviour has become a prominent social theory on health behaviour and is one of the more validated and comprehensive theories used to predict and understand exercise behaviour[i][ii]. It builds on the theory of reasoned behaviour, which we looked at last week by incorporating something called ‘perceived behavioural control’ (PBC). As such, it proposes that our health behaviours is determined by our attitudes, what we consider to be ‘normal’ (subjective norms) and how much control we think we have (PBC). We have spoken already about attitudes but here is a refresher.

Attitudes

An attitude is a personal belief that is influenced by if we think the consequences of our behaviour will be good or bad.[iii] These are influenced by how likely we feel something in as well. If we think it is likely we will get fitter and healthier by exercising and getting fitter is a good thing, we are more likely to do it.[iv]

So if you want to give yourself the best chance at exercising more this year, have a look at your attitudes toward exercise. Do you believe that exercising will benefit you? Do you believe you can achieve your exercise goals? Perhaps you could read more on the benefits of exercise.

Subjective Norms

Subjective norms are driven by social pressure to conduct a behaviour or not.[v] In essence, if we think people think we should do something, we are more likely to do it. If we think people think we shouldn’t do something, we are less likely to do it. This is thought to be driven by our need to gain approval from people we care about.[vi] This is very similar to social persuasion we discussed earlier.

How do social norms affect your exercise resolution? Are the people around you supportive of your exercise goals? Perhaps you could make friends who are supportive or elicit support from your current friends. You can do this by joining group exercise classes or exercise with your current friends.

So what is the new component, PBC?

Perceived Behavioural Control (PBC)

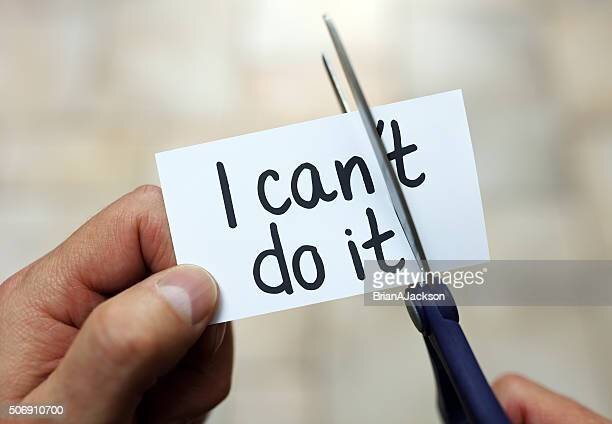

This is very similar to the concept of self-efficacy we spoke about earlier and is a reflection of how much we feel we have control over both internal and external obstacles.[vii] This recognises that there are obstacles outside our control and is useful for looking at exercise as there are often many obstacles outside our control here.[viii] The more PBC we have the more likely we are to perform that behaviour.[ix]

How can you increase your PBC? Perhaps you could break down your exercise goals into small achievable chunks. If time is a limitation, perhaps you could try to do just 10 mins of movement in the morning. That way you have done it first and it is a small enough chunk of time to be achievable. Perhaps you could hire a trainer to create a program for you. If knowledge is a barrier, perhaps you could read reputable books on exercise (or blogs like this one!) or get advice from a trainer.

Conclusion

The Theory of Planned Behaviour builds on the Theory of Reasoned Action we look at last week. It proposes that our likelihood to exercise is influenced by our attitude, social pressure and how much control we think we have over exercising.

Putting this into practice have a look at your attitudes toward exercise. How can you see exercise as a good thing and something you want to do? Have a loo at your friends, how can you surround yourself with people will encourage you to exercise and make it ‘normal’. Lastly, how do you make exercising seem to be more in your control. How can you make your goals feel more achievable.

[i] 2 cited in Downs & Hausnblas, 2005

[ii] Hagger & Chatizisarantis cited in Brooks et al, 2017

[iii] Ajzen, 1991, Co et al., 203; Glanz et al., 2008 all cited in Motalebi, Iranagh, Abdollahi & Kin, 2014

[iv] Rivis & Seeran, 2003

[v] Rivis & Sheeran, 2003

[vi] Rivis & Sheeran, 2003

[vii] Line 48 multiple sources all cited in M Motalebi, Iranagh, Abdollahi & Kin, 2014

[viii] Andrew, Smith & Biddle, 1999.

[ix] Rivis & Sheeran, 2003

Photo by Ridofranz/iStock / Getty Images